Grazing under the Giant

Go backRichie Moon looks back in time via a renovated Cerne Abbas watermeadow.

Barton Farm, the setting for one of four Cognatum estates in Dorset, is an unspoilt place, with a magnificent 14th-century Grade I tithe barn, with beautiful square-knapped flints, as its backdrop. Most of the farmland was sold off when the 24 retirement cottages were built in the early 1990s, but several acres of water meadow bordering the river Cerne, in reality little more than a chalk stream, were retained for walking and the enjoyment of the owners. Yet these pleasant meadowlands are not merely scenic. They began life as an innovative response to irrigation issues faced by local farmers in the 17th century.

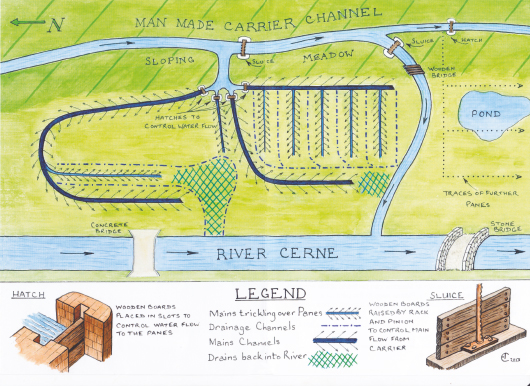

The wonderful illustration from the watermeadow leaflet showing how the panes were arranged

In the days before fresh fruit and veg from Africa and South America was flown into supermarkets, the growing season applied not just to vegetables, but to the most important crop of all for livestock farmers and horse-users alike: grass.

Being able to extend the grazing season, or the growing season for hay, could be a matter of the survival of one’s animals and indeed of the farm. From medieval times there had been attempts to extend the growing season by deliberately flooding fields to irrigate them in dry times or to protect them from the frost by blocking ditches and rivers so fields were underwater and would not freeze.

According to Historic England, most pre- 17th-century irrigation was by means of ‘floating upwards’ – blocking a watercourse, causing it to overflow and flood the surrounding farmland. Floating upwards deposited beneficial silt and provided some frost protection, but if water failed to drain off quickly, it could create anaerobic and toxic conditions which would damage the grass. More sophisticated ‘floating downwards’ systems using a constant movement of water through the grass sward allowed strict control of the flow of water on and off the meadows. Two main forms of floating downwards were used: ‘catchworks’ and ‘bedworks’, each suited to different landscapes.

Catchworks used spring water or hillside streams or farmyard run-off from a specially-constructed feeder pond to run into a contour-following ditch or ‘gutter’ which skirted the top of the meadow. When the gutter was blocked by ‘stops’ of turf, peat or logs, water overflowed down the hillside and irrigated the area of meadow below it. Lower gutters, parallel to the first, caught the water and redistributed it in a similar manner to lower pastures.

Bedworks, used on flatter river valleys, emerged at the beginning of the 17th century – the first mention of them in the UK is actually at Affpuddle in 1605. These were more sophisticated than catchworks, as we can see by looking at the example renovated at Barton Farm in Cerne Abbas, which shows clearly and on a visible scale how they worked.

John Staley, who was intimately involved in the Barton Farm renovation in 2014, wrote: ‘The water meadow was fed by water from the river Cerne diverted by a series of boards manually moved up and down in a channel called a carrier. The first sluice controlled a series of four smaller hatches supplying a flow of water to the meadow. Each section of the meadow was irrigated by a small channel, called a main, that carried the water to the crest of each ridge where it slowly overflowed and trickled down the sides (the panes) to enter a ditch and so return the water to the river (see diagram).

‘An irrigated watermeadow accelerated the growth of grass as water warmed the land, encouraging vegetation. This was a result of a steady flow of water keeping frost at bay. This early growth of grass enabled farmers to give their flocks, both cattle and sheep, “an early bite” some four to six weeks before normal pasture.

‘The watermeadows were a remarkable feat of agricultural engineering constructed entirely with hand-tools and over long hours of work. The men who did the work were known as drowners and meadmen.’

Diverting rivers so that meadows could be flooded by night and grazed by day gave a crucial extra few weeks’ grazing to local farmers, but because rivers could be blocked and unblocked at any point along their length, complex negotiations in longer river valleys would be needed so that the people at the top

of the river valley kept their drains clear and did not steal all the water from those at the bottom.

Likewise those at the bottom had to make a contribution – either physical or monetary – to keep the communal water moving. Watermeadows eventually died out for three reasons: the advances in – and the increased use of – fertilisers and crops that could be planted, the prolonged dip in sheep prices, and the introduction of tractors that could either not be used in, or would destroy the structure of, the watermeadows themselves.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the old Ministry for Agriculture Food and Fisheries (MAFF) gave grants to farmers to destroy the bedworks in their water meadows to increase productivity.

Water returning to the River Cerne

This article was first published in June 2018 edition of Dorset Life – The Dorset Magazine.

All rights reserved; reproduction without written permission forbidden.